Is it time to break up with After Affects?

How many hours have we all spent waiting for things to render? Watching frames slowly count upwards. It is like watching digital paint dry. We decided to try something different. Over 6 parts, we are going to look at what happened when we decided to break up with After Effects and embrace a new real-time workflow for ‘Back To The Future: The Musical.’

The Waiting Game

We’ve been using After Effects since we started working with video. It has always been there. It is the Swiss army knife of the video designer. We never considered that there might be an alternative and to be very honest, had not sought one out until recently. We had our set of plugins and they did what they did. But eventually the work started to look a little too much the same. We had become complacent.

We were too used to telling a director or fellow designer that it would be tomorrow before we could have that new idea rendered. We were very used to not being able to preview our work in real-time despite After Effect's best efforts. We learned how to use Dead-Line, lashing together lots of computers into render farms to speed things up. This helped a little but it was fraught with annoying problems.

This became our professional world, always watching digital paint dry while trying to make exciting things happen on stage. The piece of software at the core of our workflow was not up to the job. If it had been a media server, it would have been out the door, and a new one found. But we never asked the same question of After Effects. It was the status quo. And everyone at FRAY was very bored with the status quo.

In Steps Notch

Increasingly, we had been using Notch for creating generative content within media servers such as Disguise but we had not used it a great deal for making stand-alone video content. Our growing disillusion with After Effects coincided with us speaking at a conference where Matt Swoboda of Notch was also presenting. His message was simple, Notch is a tool designed for live video and After Effects is not, so why use it? Initially, this sounded like heresy, but the more we thought, the more it made total sense.

The thought of breaking up with After Effects, like ending any long-term relationship, was scary but we knew it was time to move on. We had a large project in the shape of ‘Back to the Future the Musical’ on the horizon which we knew would be using some generative content, so why not go the whole way? We set ourselves the rule that we would start and finish everything in Notch and only resort to After Effect or Cinema4D renders if we hit a total roadblock.

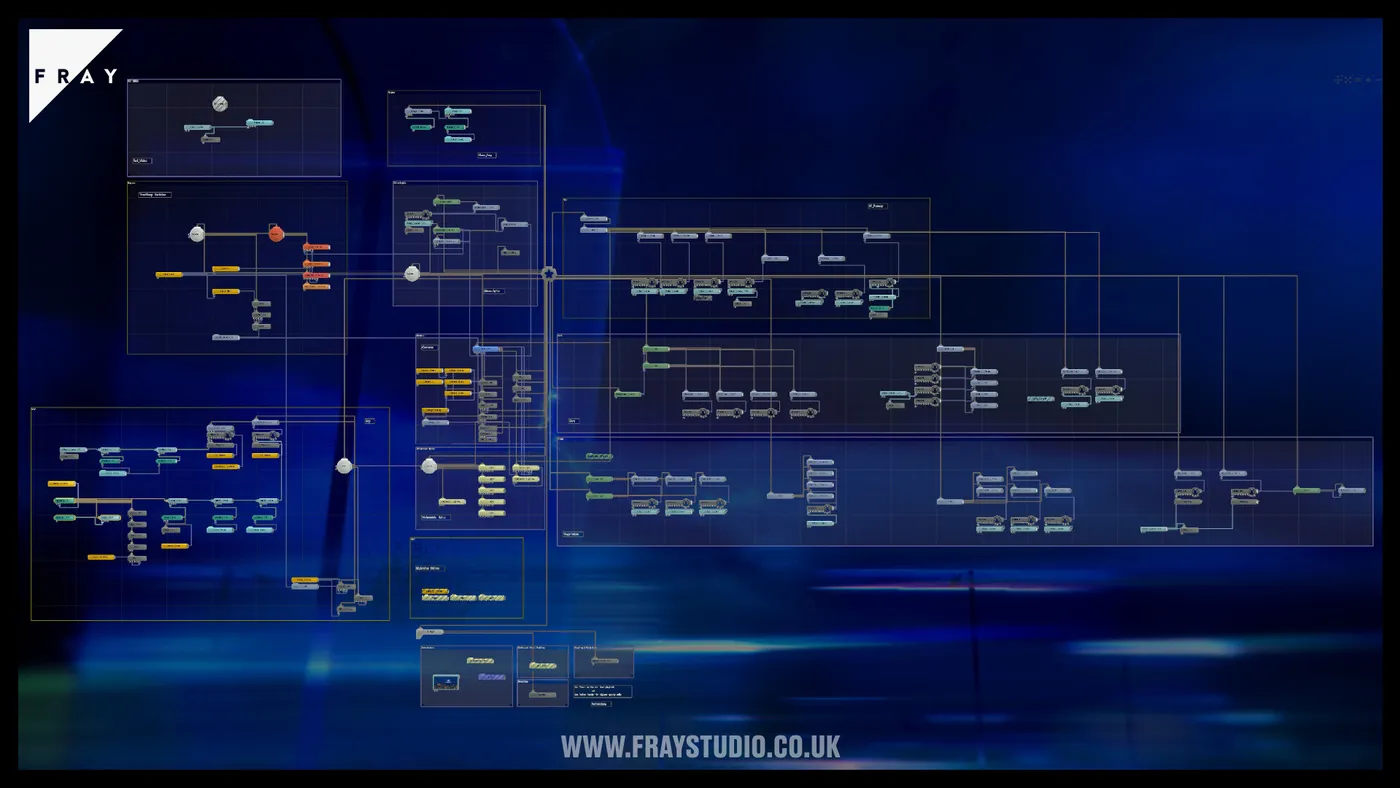

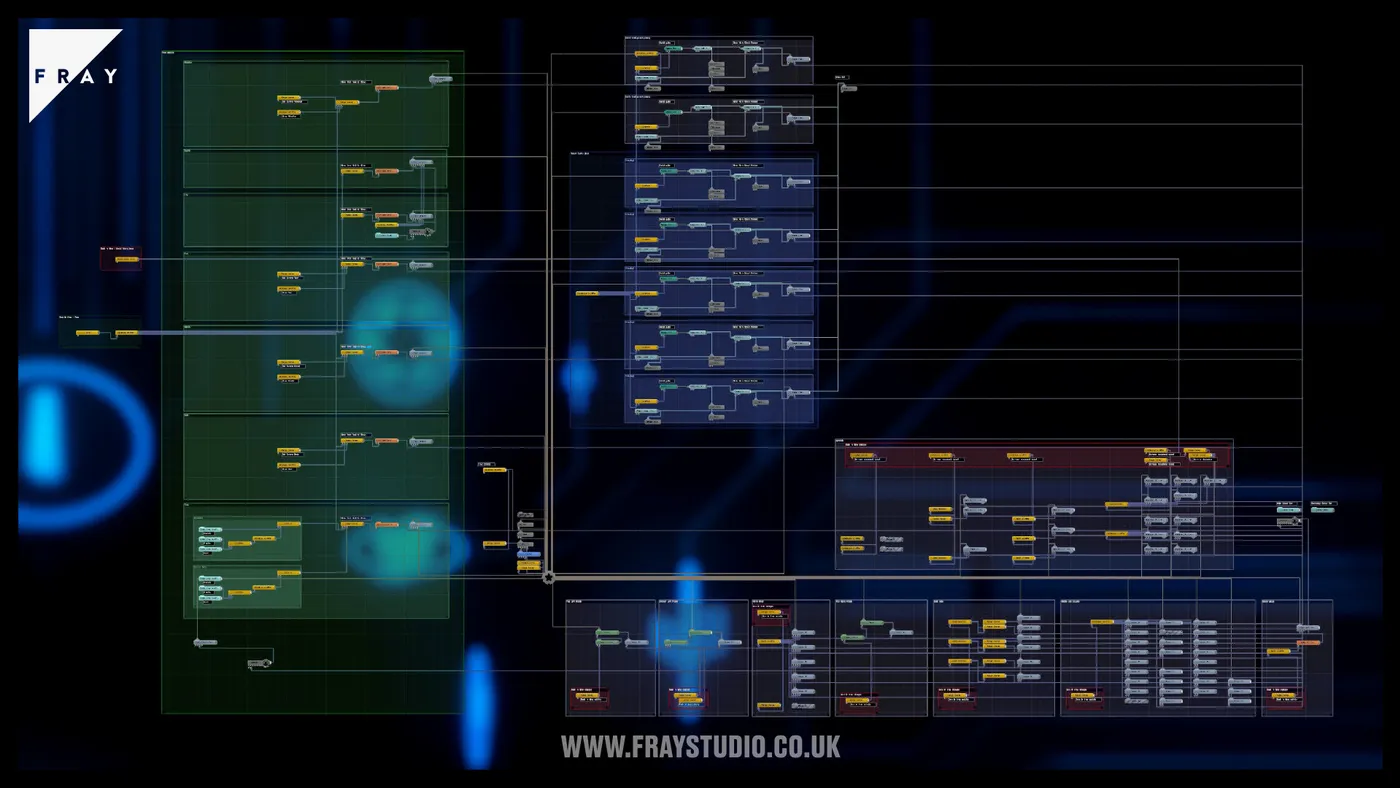

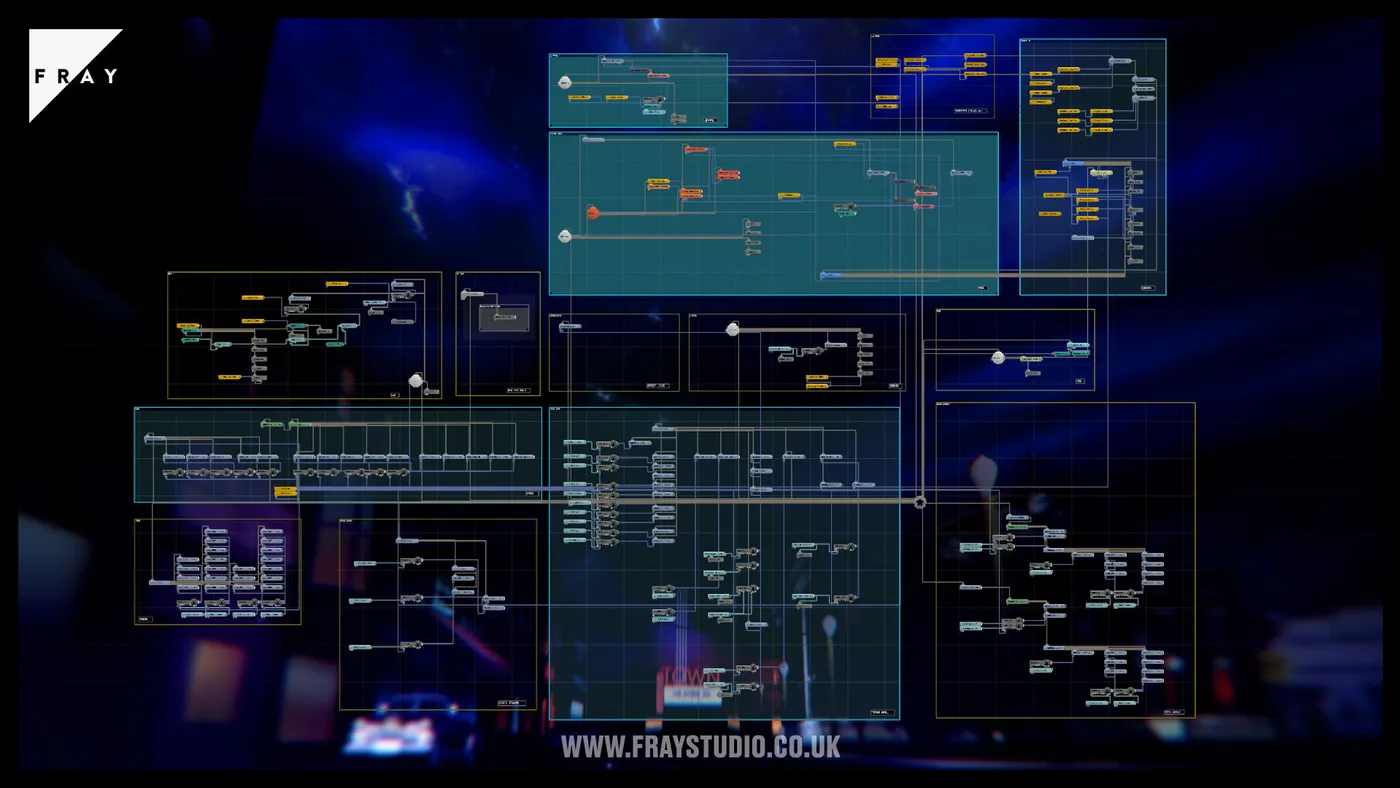

Overhauling our tried and tested studio system workflow was an exciting challenge. We had so many questions including, ‘How do we structure projects?’ ‘How do you do something in Notch you do automatically in AE?’ ‘How do you make your work accessible to others?’ ‘Is it rendered or real-time?’

Render or Real-Time?

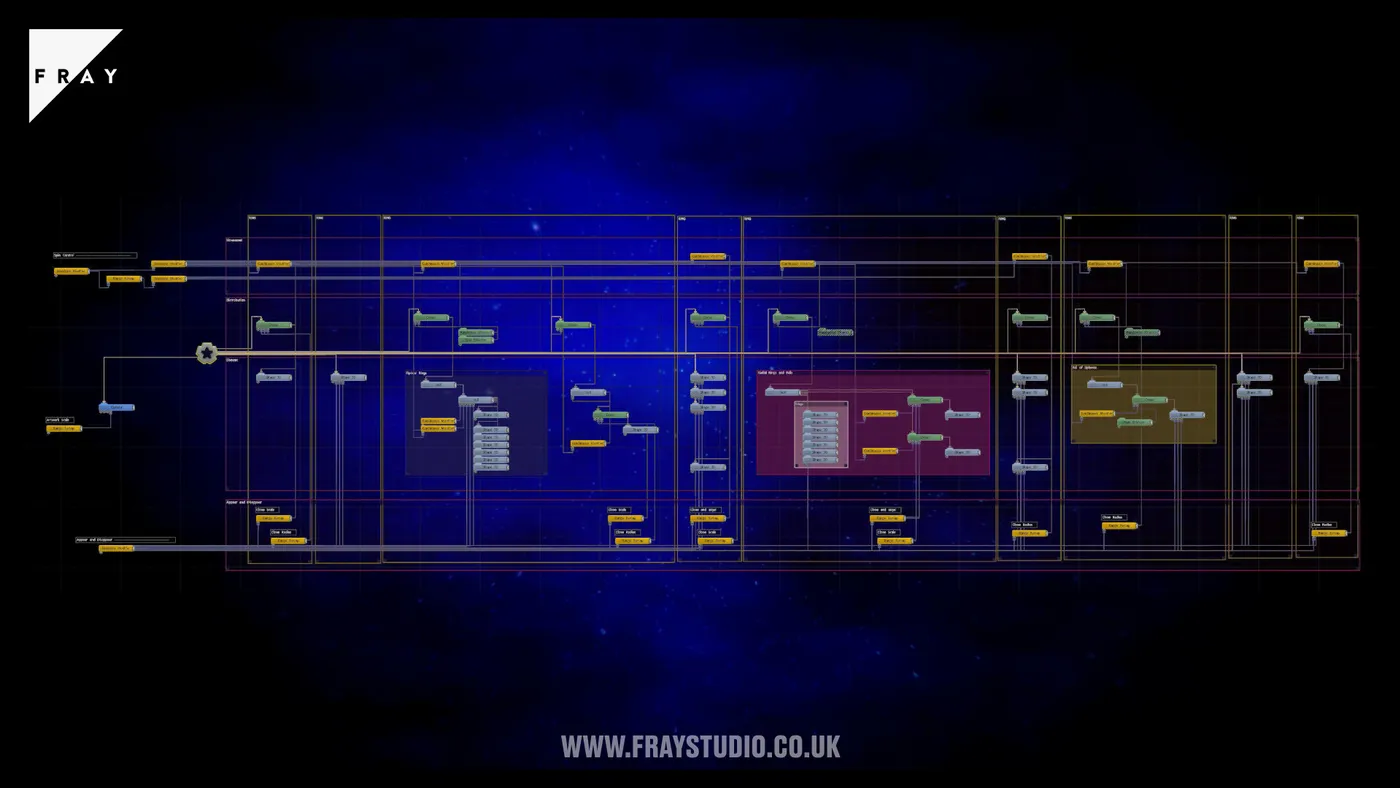

First and foremost, the rendered or real-time block question needed answering as the approach you take to making the content is very different. We decided on a few basic principals to guide us. If the video content needed to endlessly generate something like a sky, it would be a block. Variables that would change day-by-day would also be a block, and moments where animation needed to seamlessly respond to action on stage, not set by timecode, would be a block. If the moment was locked to timecode or did not need to do anything responsive, it would be rendered.

Building a block for real-time playback in the media server throws up a lot of challenges from the Notch and the Media Server perspective. We spent a lot of time looking at the performance tab. Juggling between one, significant, smart-node or several smaller, simpler nodes to find the correct balance of performance while maintaining a vibrant and exciting look. Furthermore, the generative content might be mixed with rendered content while the media server is processing automation data, dmx tables and any of the myriad of thing they can do. All meaning even less power to deliver your blocks.

Building Blocks

Once we had achieved the right performance balance for our blocks the number of blocks in our Disguise project also needed careful consideration. More blocks mean longer load times for your project and complex blocks add to this time. Ultimately, it is just a computer processing the block. Whether you are using Disguise or any other media server, it will crash at some point. You will have to restart and, if you have several servers as we did, you could be looking at upwards of 15 minutes to re-boot the whole system. The balance of what we were gaining on stage from running generative content versus the impact on our system needed constant consideration. It is easy to think generative content is the silver bullet and you will never need to wait for a computer again but this is not the case. A computer can only be taken so far before it falls over.

To balance the impact on our system, we rendered a lot of content out of Notch. And we rendered it so quickly! Not always in real-time but compared to packaging it up, sending it to a render farm in South Korea, waiting for it to render, downloading on a dodgy internet connection only to find a randomly flickering light and starting the process again, it was like moving at light speed. And once you have everything in your project turned on, even if it doesn't play in real-time 100%, it was still doing far better than After Effects ever did. Even if we had to wait 15 minutes for a sequence to render, we were still saving a ton of time. And once a 3D scene was rendered it was ready for the stage, it didn't need a final pass through After Effects to polish it up. It was a small 3D revolution.

Real-Time Render

This is not to say adapting our workflow was flawless and that we had no moments of frustration. We had to undertake a very steep learning curve for the studio. 40 years of collective Adobe experience and logic needed to be unlearned and new logics ingrained in our brains. For the 3D workflow, it was a marked improvement, but for 2D and 2.5D it was more challenging as you are working in an environment designed for 3D. Trying to create 2D composited sequences could feel like you were trying to push the software to do something it didn’t want to do. You end up with workarounds and would occasionally find yourself wondering if it would be easier just to fire up After Effects.

Notch is also not great at editing a sequence together in terms of laying out a series of pre-compositions on a timeline. The timeline is not as clean and intuitive as After Effects but After Effects have had 20+ years to perfect this so we could forgive the shortcomings. In the past few releases of Notch you can see the software progressing rapidly. What has actually changed in After Effects recently? Very little of note. The major advantage which out weighs all the frustrations? The near-instant render times. Hours of productivity regained as you no longer had to wait for an eternity to see the result, it was all time that you could spend creatively, for the benefit of the show.

Time to Move On

Changing our workflow on this project permanently turned a light bulb on for us. Yes, Notch is not perfect, but nor are the tools we are all used to. In the end, we landed at around 75-80% of the show having been made within Notch. Lack of long-term experience and familiarity partly accounts for our falling short of 100%, but there are also some limitations we just couldn’t overcome. But we are ok with this. It was an experiment that had very positive results. We achieved far more than we had hoped and genuinely felt liberated from the old way of working. We made a significant step towards a faster and more intuitive workflow based around allowing creativity to come to the forefront and not being held back by technology.

This is a brave new world of real-time workflow, and while it has come leaps and bounds in recent times, it is far from a finished project. There is tremendous promise there and, as a creative community, we need to embrace these tools to help develop them together to make software truly fitting for the live-video community.